BIG IDEA:

FAITH THAT PATIENTLY PERSEVERES AVOIDS THREE DANGERS BY THE PROPER FEAR OF GOD

INTRODUCTION:

Craig Blomberg: Many commentators end the body of the letter at 5:6, but this appears a singularly inappropriate place for so major a break. Vv. 1–6, after all, sketch the key trial that has caused all of the others discussed in this book, while vv. 7–11 (and, we will argue, v. 12 as well) present the proper response James’s audience is to offer to these difficult circumstances. These twelve verses, therefore, belong closely together.

Responding to Oppression (5:1–12)

A. Christians should not try to wreak vengeance on their oppressors because God has promised to take care of that (vv. 1–6).

- The rich oppressors are called to lament their coming miseries (v. 1).

- Their judgments are enumerated (vv. 2–3b).

- Their sins of oppression are illustrated (vv. 3c–6).

B. Christians should respond to oppression with a persevering and prophetic patience (vv. 7–11).

- Christians can remain patient because the judgment day is near (vv. 7–9).

- Christian patience must be persevering and prophetic (vv. 10–11).

- Christians must persevere in faith until they see God’s great compassion (v. 11).

C. Christians should not be tempted to fend off creditors with unrealistic promises (v. 12).

- They should not promise what they can’t deliver (v. 12a).

- They should be individuals of impeccable integrity (v. 12b).

Main Idea: Christians should respond to oppression not by usurping God’s role as avenger, nor by making unrealistic promises to their oppressors, but with a persevering and prophetic patience. Only God can fully and fairly right all wrongs, and he has promised to do so at the Parousia. . .

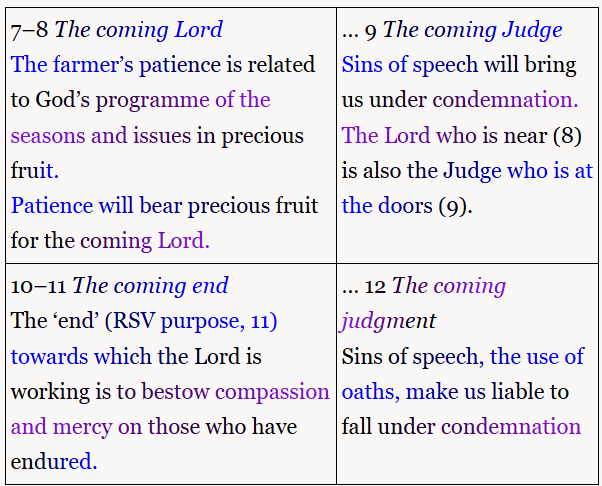

What James’s church members should not do, however, is make vows. These likely involved promises to pay off debts if only they could be given more loans or more time, in ways that probably often simply exacerbated the problem. Christians should be people of such integrity that their words may simply be trusted (v. 12). By introducing this verse with “above all,” James demonstrates that it is the climax of this treatment of proper responses to oppression. Once again, it is speech that forms the heart of how one behaves, rightly and wrongly. Indeed, we may think of vv. 7–12 as even more tightly knit together: vv. 7–8 command patience; v. 9 warns against the wrong use of the tongue (grumbling); vv. 10–11 then illustrate patience; and v. 12 again warns against the wrong use of the tongue (oaths). But this time, the positive flipside appears as well. Most important of all is verbal integrity.

David Platt: James’s emphasis on the poor leads to the harshest language in the entire book. The tone at the end of chapter 4 has carried over into the rebuke of the rich in these verses. James emphasizes the fact that the judgment of God is coming soon. Verse 1 mentions “miseries that are coming,” verse 3 refers to the “last days,” and verse 5 alludes to a “day of slaughter.” This emphasis on God’s end-time judgment continues in verses 7-9: James says to “be patient until the Lord’s coming” (v. 7); in verse 8 he says that “the Lord’s coming is near”; then in verse 9 we learn that the “judge stands at the door!” Jesus is coming back, and He’s going to do at least two things.

- He is coming to judge the sinful.

- He is coming to deliver the faithful.

John MacArthur: As noted throughout this commentary, James was presenting tests of genuine saving faith, tests which validate or invalidate one’s claim to be a Christian. Building on the teaching of our Lord, as he often does, James presents another such test in chapter 5—that of how one views money. The first six verses of chapter 5 form a strong rebuke—the strongest in the entire epistle. James’s blistering, scathing denunciation condemns those who profess to worship God but in fact worship money. He calls on them to examine the true state of their hearts in light of how they feel about their wealth. . .

Though primarily addressed to those rich fakers in the church who professed allegiance to Christ but actually pursued riches, James’s warning is a timely one for Christians as well. Believers must be wary of falling into the same sins that characterize unbelievers. James shows the sin of loving money to all so none will fall into it. . .

In verses 7–11 he shifts his focus from the persecutors to the persecuted, moving from condemning the faithless, abusive rich to comforting the faithful, abused poor. James also instructs the suffering poor as to what attitude they are to have in the midst of persecution. The theme of this section is defining how to be patient in trials. . .

James gives six practical perspectives enabling believers to patiently endure trials: anticipate the Lord’s coming, recognize the Lord’s judgment, follow the Lord’s servants, understand the Lord’s blessing, realize the Lord’s purpose, and consider the Lord’s character.

R. Kent Hughes: Though this is a characterization of the world without Christ, we must never imagine ourselves to be immune. We must each ask ourselves: Do I hoard? Am I guilty of overaccumulation of wealth? Have I ever or am I now defrauding someone? Is there financial deception in my life? Have I succumbed to the culture’s Siren song of self-indulgence? Are there sub-Christian excesses in my life? Have I “murdered” another—that is, have I victimized someone because of a power advantage I possess?

I. (:1-6) THE DANGER OF FILTHY RICHES

David Nystrom: James provides four reasons for the wealthy landowners to weep:

- Their wealth is temporal and subject to the ravages of time;

- they are guilty of a crime against their sisters and brothers;

- they will be judged and condemned for this selfish use of temporal goods;

- and they have been adding to their material treasure as if the world will go on forever.

Douglas Moo: The rich people pictured are clearly wealthy landowners, a class accused of economic exploitation and oppression from early times. In James’ surroundings, we may think particularly of Palestinian Jewish landlords who owned large estates and were often concerned only about how much profit could be gained from their lands. James proceeds to announce the condemnation of these rich landholders (v. 1) and justifies their condemnation on the grounds of their selfish hoarding of wealth (vv. 2–3), their defrauding of their workers (v. 4), their self-indulgent lifestyle (v. 5) and their oppression of ‘the righteous’ (v. 6).

Why does James preach this message of denunciation of non-Christians in a letter addressed to the church? Calvin appropriately isolates two main purposes:

- James ‘… has a regard to the faithful, that they, hearing of the miserable end of the rich, might not envy their fortune,

- and also that knowing that God would be the avenger of the wrongs they suffered, they might with a calm and resigned mind bear them’.

A. (:1) Summary: It’s Payback Time for the Filthy Rich!

“Come now, you rich, weep and howl for your miseries

which are coming upon you.”

Speaking against those who had gained wealth in unethical ways and then had used that wealth in selfish ways; stresses the certainty of the judgment

Curtis Vaughan: anguish for impending judgment

Alec Motyer: But who are these rich people? Are they Christians who have been so drawn off course by the power wealth bestows that they have turned to oppress their fellow-believers? It may sadly be so, for there has surely been no period in church history when James’ strictures against the rich would not apply to some church members. In support of the view that James is addressing rich Christians, we may note that this is suggested by the opening words of verse 1, where Come now, you rich is parallel with Come now, you who say in 4:13, and since the latter are Christian business folk, why should not the former be wealthy Christians? . . .

Commentators who argue against interpreting the rich as members of the church urge, for example, that there is no call to repentance (LAWS, ADAMSON), nor any holding out of an expectation of salvation but only of judgment to come (KNOWLING).

R.V.G. Tasker: Assuming their unrepentance he announces, in the spirit of the Old Testament prophets, the inevitable doom that confronts them. And the inference he would wish his Christian readers to draw from this denunciation is the folly of setting a high value upon wealth, or of envying those who possess it, or of striving feverishly to obtain it. For the truth is that all who are rich without having ‘poverty of spirit’ are faced, whether they are aware of it or not, with swift and sure retribution at the hands of God. Because the rich are nearly always self-deceived, by thinking that their present prosperity will be permanent, James warns them that miseries are coming upon them. And because they imagine that by means of their wealth they can mitigate, if not render themselves immune from the sorrows and hardships that are the lot of others, James bids them weep and howl at the severity of the divine retribution which will fall upon them. This judgment has not already arrived; but it is so certain and so predetermined that James, in true prophetic manner, speaks of it almost as if it were a present reality, for the literal meaning of the original is that these miseries are now in the process of coming upon them.

John Painter: The sins of those who actually are rich are more seriously unscrupulous and exploitative, and James’s criticisms are correspondingly stronger, using graphic terms to describe the end of the rich. . . There is a piling up of language rarely used in the NT . . . This multiplication of the language of despair and disaster communicates an overwhelming sense of distress and anguish. . .

This tirade may also function to dissuade any who are tempted by the attraction of the way of the rich. Wealth has its place, but if it is hoarded for selfish satisfaction, it will not only fail to do the good that might be achieved but will also fail to satisfy the hoarders.

David Nystrom: These wealthy people must “weep and wail.” “Weep” (klaio) means to respond to disaster in a rightful manner—to weep from the depths of one’s being in grief and remorse. “Wail” (ololuzo) means to howl, especially as a result of sudden and unexpected evil and regret (see Isa. 15:2–3, 5; Jer. 13:7; Lam. 1:1–2 as Old Testament parallels). This remorse is justified because the lot of these rich is “misery” (talaiporia, a word used only here and in Rom. 3:16 in the New Testament). James may indeed have Jeremiah 12:3 within view: “Set them apart for the day of slaughter.” The reason is not their wealth per se, but the fact that they have not sought to use their wealth to alleviate the sufferings of the poor. In fact, their desire for wealth is the cause of much of this suffering in a direct fashion, for the poor work for the landowners.

B. (:2-3a) You Can’t Take it With You / Even Riches Don’t Last Forever

- Rotten

“Your riches have rotted“

cf, storehouses of corn and grain going bad

- Ruined

“and your garments have become moth-eaten“

- Rusted

“Your gold and your silver have rusted“

John Painter: The rusted, unused, wasted resources are evidence against the rich of their heartless disregard for the poor, of their unwillingness to come to the aid of the poor, to provide alms. Matthew 6:19–21 and Luke 12:33–34 provide sayings about storing up treasures on earth, where moth and rust consume, and a number of parables add their critique, such as the parable of the rich fool, who built bigger barns to store up an excessive harvest (Luke 12:13–21), and the parable of the rich man and Lazarus (Luke 16:19–31). The first shows the folly of hoarding wealth and not using it for a good purpose (“You fool! This night your life will be taken from you!” Luke 12:20). Note also “Every work decays and ceases to exist, and the one who made it will pass away with it” (Sir. 14:19). The second parable condemns the rich man for willful disregard of the plight of the poor man, narrating their reversal of fortunes in the “afterlife” beyond death. The fate of the rich man is described in Luke 16:22–28. He is in torment, in agony in the flames, his tongue hot and dry, while Lazarus is in paradise, in Abraham’s bosom. This image of torment in the flames seems to be a variant on the notion of the rust of wasted resources eating into the flesh like fire. For James, hoarded wealth is wasted; it is evidence of the heartlessness of the rich, and the dissolution (rust) will fuel the fire of their torment.

Douglas Moo: All three statements in verses 2–3a, in fact, reflect the traditional Old Testament and Jewish teaching about the foolishness of placing reliance upon perishable material goods.

C. (:3b) Your Hoarding of Wealth Will Come Back to Haunt You

- Evidence that Demands a Verdict

“their rust will be a witness against you“

Ralph Martin: While they think that the wealth accumulated is held as a perpetual possession, they are vulnerable to severe judgment because not only is such wealth temporary, but it is the witness whose testimony condemns the rich. Instead of sharing their wealth with the needy (a response already spoken of as a sign of a saving faith in 2:14–16) they hoard it; what makes this doubly tragic is that they do so in the last days and thus underline the folly of their actions.

- Conspicuous Consumption

“and will consume your flesh like fire”

- Bad Timing

“It is in the last days that you have stored up your treasure!”

Alec Motyer: Hoarding is a denial of proper use (cf. Lk. 12:33), of true trust (cf. 1 Tim. 6:17) and of godly expectancy (cf. 1 Tim. 6:18–19).

Douglas Moo: As those who live in these ‘last days’, we, too, should recognize in the grace of God already displayed and the judgment of God yet to come a powerful stimulus to share, not hoard, our wealth.

Thomas Lea: James thundered warnings of judgment on the stingy, greedy landlords who preferred to collect money rather than help the poor and needy. The generosity and unselfishness of early Christians provided visible solutions to the problems of hunger, need, and greed which they confronted (see Acts 4:32–37).

Daniel Doriani: Material wealth only temporarily quenches the soul’s thirst for meaning and acceptance. Acquiring wealth to cure the problem of meaninglessness is like drinking coffee to solve the problem of exhaustion. It can mask the problem, but it cannot cure it. Riches cannot fulfill the quest for meaning, but those who live for wealth decide the problem is not wealth per se, but their insufficient wealth. Thus, devotees of wealth work harder and harder at the wrong thing. The desire for wealth becomes insatiable. If anyone thinks riches or social rank will satisfy his soul, he deludes himself.

- Does anyone hope wealth will gain him respect? In our achievement-oriented society, as soon as our performance falters, honor plummets. (Consider the way a failed presidential candidate is treated in the media.) Lasting respectability really comes from our creation in the image of God.

- Does anyone hope wealth will gain her acceptance? In society, any flaw can spoil our rank, but God accepts us whatever our flaws may be, if we trust in him.

- Does anyone hope wealth will gain him significance? We cannot find permanent significance in impermanent things. We find significance by joining the kingdom and the cause of God.

D. (:4) Your Exploitation Has Not Gone Unnoticed

“Behold, the pay of the laborers who mowed your fields,

and which has been withheld by you, cries out against you;

and the outcry of those who did the harvesting

has reached the ears of the Lord of Sabaoth.”

William Barclay: The selfish rich have gained their wealth by injustice. The Bible is always sure that the laborer is worthy of his hire (Luke 10:7 1 Timothy 5:18). The day laborer in Palestine always lived on the very verge of starvation. His wage was small; it was impossible for him to save anything; and if the wage was withheld from him, even for a day, then literally he and his family would not eat.

Curtis Vaughan: In Psalm 46:7, 11 the title is used in a context declaring God to be the Saviour and Protector of His people. Its use in James points up that none other than the omnipotent God to whom all the hosts of the universe are subject is the Avenger and Protector of the poor.

Warren Wiersbe: Note the witnesses that God will call on that day of judgment.

- First, the rich men’s wealth will witness against them (5:3).

- The wages they held back will also witness against them in court (5:4a).

- The workers will also testify against them (5:4).

John Painter: Here the rich are depicted as exploiting their workers, withholding their wages. For the rich to do this was heartless and unscrupulous, creating great hardship for the poor. The law explicitly forbade this practice: “The wages of the workers shall not remain with you until morning” (Lev. 19:13). Vividly, James depicts these withheld wages as crying out, along with the cries of the unpaid workers rising to the ears of the Lord of hosts. The presence of what should have been paid to the workers, retained unjustifiably by the rich landowners, was damning evidence and, with the cries of the workers, called for justice.

David Nystrom: [:4-6] James now lists specific behaviors that have contributed to the hoarding of wealth.

- For one thing, they have not paid their hired laborers their due, thereby robbing their own neighbors of earned pay.

- In verse 5 James turns his attention from the hardship imposed on others to the ease and sloth of the wealthy. He levies two allegations:

(1) They have lived lives of “luxury” and gross “indulgence.”

(2) The final accusation aimed at the landed class is their plotting of the wrongful treatment and even murder of the innocent (v. 6).

E. (:5) Your Hedonism Has Set You Up for Stricter Judgment

- You Have Lived High Off the Hog

a. “You have lived luxuriously on the earth“

Douglas Moo: The pursuit of a luxurious lifestyle that is selfish and unconcerned about others’ needs is the third accusation brought against the rich. They have lived on earth in luxury and self-indulgence. The Greek for this phrase has two verbs. The latter one translates a form of spatalaō, which occurs in biblical Greek elsewhere only in 1 Timothy 5:6 and in Ezekiel 16:49. In the Ezekiel text, the people of Sodom are condemned for being ‘arrogant, overfed and unconcerned’, and for failing to help ‘the poor and needy’. Lived… in luxury translates a form of tryphaō. Peter uses the noun cognate to this verb to refer to the daytime ‘revelling’ in which depraved false teachers delight (2 Pet. 2:13). Even the easily overlooked phrase on earth bears clear negative connotations, suggesting a contrast between the pleasures the rich have enjoyed in this world and the torment that awaits them in eternity.

b. “and led a life of wanton pleasure“

William Barclay: The selfish rich have used their wealth selfishly. They have lived in soft luxury, and have played the wanton. The word translated to live in soft luxury is truphein. Truphein comes from a root which means to break down; and it describes the soft living which in the end saps and destroys a man’s moral fibre; it describes that enervating luxury which ends by destroying strength of body and strength of soul alike. The word translated to play the wanton is spatalan; it is a much worse word; it means to live in lewdness and lasciviousness and wanton riotousness. It is the condemnation of the selfish rich that they have used their possessions to gratify their own love of comfort, and to satisfy their own lusts, and they have forgotten all duty to their fellow-men.

Alec Motyer: Worldly wealth is an area of high risk in the battle to walk humbly with God. It is hard to be rich and lowly at the same time. The use of money and the life of self-pleasing are never far apart.

- You Have Fattened Yourself for the Day of Slaughter

“you have fattened your hearts in a day of slaughter“

Ralph Wilson: Though the actual event of catastrophic judgment is yet to begin, for this letter the death-knell of the rich has already sounded. The wealthy indulge themselves and ignore the poor as if the day of slaughter (that “great judgment day,” Mussner, 197) were not only far away but did not exist at all!

F. (:6) Your Bully Tactics Will Now Be Avenged

“You have condemned and put to death the righteous man;

he does not resist you.”

The rich did not fear God and did not think they would be held accountable for their behavior. They placed all of their security in their wealth.

Charles Ryrie: This probably refers to the practice of the rich taking the poor (“the righteous“) to court to take away what little they might have, thus “murdering” them.

Douglas Moo: Innocent could also be translated ‘righteous’ (dikaion), and some interpreters think that this ‘righteous one’ might be Jesus, or perhaps even James ‘the Just’ (or ‘righteous’) himself (assuming, of course, that a later writer has used James’ name). The context and the traditions that James is using suggest another meaning, however: a generic reference to righteous people who are being persecuted by the rich. These people are ‘poor and needy’ and trust in God for deliverance.

II. (:7-11) THE DANGER OF COMPLAINING AGAINST YOUR BROTHER

Alec Motyer: Balanced Structure of 5:7-12

In this way we see that not only do sections on patience and speech alternate, but that sections dealing with joyful hope (7–8) and (10–11) lead into sections dealing with fearful expectation (9), (12). The whole unit (7–12) is, in fact, wonderfully symmetrical and balanced.

A. (:7a) Summary: Be Patient (as you anticipate the soon return of the Lord)

“Be patient, therefore, brethren, until the coming of the Lord.”

George Guthrie: The passage at hand is connected to the previous unit on the guilt of the wicked wealthy (5:1–6) by the word “therefore” (NASB; oun), indicating that judgment on the rich serves as a basis for encouragement to the righteous. On this basis they are to “be patient” (makrothymeō, GK 3428), a term connoting enduring under provocation or waiting with a right attitude (1Co 13:4; 1Th 5:14; Heb 6:15; 2Pe 3:9). It is almost synonymous with hypomonē (GK 5705), used in both its verbal and nominal forms in v.11. It may be that life’s hardships in general are in mind (Ropes, 293), but James specifically ties the exhortation back to 5:1–6 and thus seems to have patience under injustice or oppression in view.

Douglas Moo: The transition from denunciation of rich non-Christians to encouragement of believers is signalled by James’ return to his familiar address: brothers and sisters. Then (oun) shows that this encouragement is based on the prophetic condemnation of wicked, rich oppressors in 5:1–6: since God will punish these oppressors, the believers need to wait patiently for that time. Patience is clearly the key idea in this paragraph.

R. Kent Hughes: Three great words in the New Testament refer to the Lord’s second coming. Epiphania means an appearing or a showing or a manifestation of Christ. Another great word is apokalupsis, which means an unveiling, a laying bare, a revelation, and refers to the full display of Christ’s power and glory. The third word, the one for the Lord’s “coming” in verses 7, 8 of our text, is parousia, which emphasizes Christ’s physical presence, literally meaning “being alongside of.” It is used in this way fifteen times in the New Testament in reference to Christ’s return, denoting “the physical arrival of a ruler.” The significance of the word as James uses it here is that his suffering people longed for the presence of Christ their King. They knew that when Jesus came to be with them, everything would be all right.

B. (:7b) Example of the Patience of the Hard Working Farmer

(Looking forward to the harvest; trusting in divine providence)

“Behold, the farmer waits for the precious produce of the soil,

being patient about it, until it gets the early and late rains.”

David Nystrom: As a practical illustration of such patience, James refers to a farmer who waits patiently for harvest time and for the autumn and spring rains. In the eastern Mediterranean two seasons of rain are normal and necessary for a successful crop. The emphasis here is double, not only on patience, but also on the surety of the farmer that the rains and the harvest will indeed come, each in its due season. This waiting is hard psychologically, for in the presence of the vagaries of weather that determine the success of the crop, the farmer is helpless. But the waiting also involves a good deal of hard work and encounters with the vicissitudes of normal existence.

Craig Blomberg: The early and late rains were standard climatic features of the eastern half of the Mediterranean basin, familiar to the readers. The early rains normally lasted from mid-October to mid-November, while the late rains spanned key portions of March and April. Thus the two main harvest (and planting) seasons came in fall and spring. Farmers, however, hardly sat idle in between, but rather worked hard in weeding, hoeing, fertilizing, and doing whatever they could to bring their crops to full fruition. James’s analogy would have resonated deeply with his audience, many of whom were clearly farmers.

Peter Davids: The picture is that of the small farmer in Palestine, not the hired laborers of 5:4 (ἐϱγατής), who were often once small farmers and dreamed of yet owning land, but who were either not the firstborn or had lost their land to large landholders due to hard times. The small farmer plants his carefully saved seed and hopes for a harvest, living on short rations and suffering hunger during the last weeks. The whole livelihood, indeed the life itself, of the family depends on a good harvest: the loss of the farm, semistarvation, or death could result from a bad year. So the farmer waits for an expected future event (ἐϰδέχεται); no one but he could know how precious the grain really is (τòν τίμιον ϰαϱπòν τῆς γῆς is one indication that the author has a small farmer in view; cf. Mussner, 202). He must exercise patience no matter how hungry he is (μαϰϱοθυμῶν), for he waits with a view toward the coming harvest (ἐπ’ αὐτῷ). This patience must last “until he receives the early and late rain.”

William Barclay: The early Church lived in the expectation of the immediate Second Coming of Jesus Christ; and James exhorts his people to wait with patience for the few years which remain… the early rain was the rain in late October and early November; without it the seed which had been sown would not germinate at all. The late rain was the rain of April and May, without which the grain would not mature. The farmer needs patience to wait until nature does her work; and the Christian needs patience to wait until Christ comes.

Ralph Martin: James, on the other hand, makes much of the interval “between the times,” specifically employing the horticultural allusion to sowing and reaping and enforcing the need to wait in patient hope for the harvest of divine judgment and redemption to come. There is no way the readers can accelerate the arrival of that day (contrast 2 Pet 3:12). In fact the opposite is the needful reminder: only in God’s good time and way will the end come. The Judge is already at the door, but the exact time when the decisive moment (kairos) of eschatological deliverance (for the poor) and doom (for the rich, 1:10–11; 4:9–10; 5:1–6) comes is not to be hastened; it can only be awaited. Any other disposition is not only frowned upon and treated as useless (as an impatient farmer who cannot wait for harvest will always be disappointed); it is positively injurious, ἵνα μή κριθῆτε, lit., “lest you be judged.”

C. (:8) Summary Repeated: Be Patient

(as you anticipate the soon return of the Lord)

“You too be patient; strengthen your hearts,

for the coming of the Lord is at hand.”

Douglas Moo: As the farmer waits patiently for the seed to sprout and the crops to mature, so believers must wait patiently for the Lord to return to deliver them and to judge their oppressors. And while they wait, they need to stand firm (lit. ‘establish your hearts’). Paul gave the same exhortation to the Thessalonians as they awaited the parousia (1 Thess. 3:13; cf. 2 Thess. 2:17), and the author to the Hebrews claimed that ‘it is good for our hearts to be strengthened by grace’ (Heb. 13:9). What is commanded, then, is a firm adherence to the faith in the midst of temptations and trials. As they wait patiently for their Lord to return, believers need to fortify themselves for the struggle against sin and difficult circumstances. . .

The accusation that James has erred on this matter rests on the supposition that James believed that the parousia must necessarily occur within a very brief period of time. But there is no reason to think that this was the case. The early Christians’ conviction that the parousia was ‘near’, or ‘imminent’, meant that they fully believed that it could transpire within a very short period of time, not that it had to. They, like Jesus, knew neither ‘that day or hour’ (Mark 13:32), but they acted, and taught others to act, as if their generation could be the last. Almost twenty centuries later, we live in exactly the same situation: our own decade could be the last in human history. And James’ advice to us is the same as it was to his first-century readers: be patient and stand firm!

Ralph Martin: That summons to ὑπομονή (a term frequent in the Testament of Job, where Job’s wife Sitis is the chief complainant, e.g., chaps 24, 25, 39, and Satan is given a prominent role as tempter: see R. P. Spittler in J. H. Charlesworth, The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha 1:829, 834, 836 on the origin of this in Jewish and Christian sectarian teachings) is the main facet of Job’s experience on which James fastens in order to drive home the single point that his readers should learn how to see their troubles as part of God’s design (τέλος). Like the canonical Job they will be brought to vindication (4:10) only if they maintain this faith and fortitude and endure to the end. Job 27:7 could well be James’ motto as well as Job’s: “Now then, my children, you also must be patient in everything that happens to you. For patience is better than anything.”

D. (:9) Warning Against Complaining (in light of the soon return of the Lord)

“Do not complain, brethren, against one another,

that you yourselves may not be judged;

behold, the Judge is standing right at the door.”

Cf. how the Israelites grumbled against their spiritual leaders when confronted with difficult trials

John Painter: This is both an assurance to those who have strengthened the resolve of their hearts and a threat to those who grumble and complain about their brothers (and sisters) and to those who exploit the righteous poor. This sense of imminent judgment undergirds the forceful warning in 5:1–6. Very likely the Jesus tradition underlying this development is found in Matt. 7:1–5, which begins, “Do not judge lest you be judged.” This warning is especially pressing because the judge has drawn near and stands at the door (see Mark 13:29).

Douglas Moo: The meaning may be that believers should not grumble to others about their difficulties, or that believers should not blame others for their difficulties (cf. NLT). Perhaps James intends both ideas. Once more, however, biblical usage might suggest a further allusion. The verb stenazō (grumble) regularly refers to the ‘groaning’ of the people of God under oppression; see, for example, Exodus 2:23: ‘The Israelites groaned in their slavery and cried out, and their cry for help because of their slavery went up to God.’ This biblical allusion strengthens the supposition that the grumbling James warns about has arisen because of the pressure of difficult circumstances.

John MacArthur: Living with difficult circumstances can cause believers to become frustrated, lose patience, and complain … against one another, especially against those who appear to be suffering less than they are or who seem to be adding to their trouble. Stenazō (complain) also means “to groan within oneself,” or “to sigh.” It describes an attitude that is internal and unexpressed (cf. Mark 7:34; Rom. 8:23). It is a bitter, resentful spirit that manifests itself in one’s relationships with others.

Daniel Doriani: But we must notice a certain twist. So far, James has referred to Christ’s return to encourage believers to stand firm under duress. But now he bids us to remember the coming judgment whenever we would grumble against each other. Christians will not face God’s wrath on judgment day, but we will face God’s assessment of every word and every deed (Matt. 12:34–37; 2 Cor. 5:10). As Peter Davids says: “The nearness of the eschatological day is not just an impetus to look forward to the judgment of ‘sinners’ . . . , it is also a warning to examine one’s own behavior so that when the one whose footsteps are nearing finally knocks on the door, one may be prepared to open, for open one must, either for blessing or for judgment.”

Craig Blomberg: Whatever one’s views on the disputed concept of degrees of eternal reward in heaven, at the very least these believers risk more severe censure and less hearty praise from Christ on the judgment day (cf. 1Co 3:14–15; 2Jn 8).

E. (:10-11) Remember the OT Examples of Endurance

- Example of the Godly Prophets

“As an example, brethren, of suffering and patience,

take the prophets who spoke in the name of the Lord.

Behold, we count those blessed who endured.”

R. J. Knowling: Patience is the self-restraint which does not hastily retaliate against a wrong, and steadfastness is the temper which does not easily succumb under suffering.

John MacArthur: The rejection of God’s spokesmen is a familiar and tragic theme in Israel’s history. Jesus denounced the Pharisees as the “sons of those who murdered the prophets” (Matt. 23:31). Later in that chapter, Jesus described Jerusalem (symbolic of the entire nation of Israel) as the city “who kills the prophets and stones those who are sent to her” (v.37). Stephen, on trial before the Sanhedrin, challenged them,” Which one of the prophets did your fathers not persecute? They killed those who had previously announced the coming of the Righteous One, whose betrayers and murderers you have now become” (Acts 7:52; cf. Neh. 9:26; Dan. 9:6).

- Example of Job

“You have heard of the endurance of Job“

William Barclay: Job’s is no groveling, passive, unquestioning submission; Job struggled and questioned, and sometimes even defied, but the flame of faith was never extinguished in his heart.

Ralph Martin: Job’s example offers the Christian hope because it becomes apparent from the biblical story that Christians can withstand adversity. By examining Job’s life, the readers may appreciate that there was a purpose behind what happened to him (again the sovereignty of God is in view; see 4:15). Job came to understand God’s faithful nature (Job 42:5) before his material possessions were restored, and as he persevered, he found his closest communion with God in the midst of adversity.

R. Kent Hughes: What an encouragement to know that God does not expect stoic perseverance in the midst of trials. He knows we are clay. He understands tears. He accepts our questions. But he does demand that we recognize our finiteness and acknowledge there are processes at work beyond our comprehension. A plan far bigger than us is moving toward completion. And God demands that we, like Job, hold on to our faith and hope in God.

- Examples of the Compassion and Mercy of God

“and have seen the outcome of the Lord’s dealings,

that the Lord is full of compassion and is merciful.”

The anticipated return of the Lord as the Judge should give us all a proper fear of the Lord and the necessary patience to endure suffering rather than to complain against perceived mistreatment by our brothers.

David Nystrom: Finally, the purpose and plan of God includes his “compassion and mercy.” We have seen these themes before (4:6), but James knows that human beings are not only in constant need of the assurance of grace and forgiveness, but also in constant need of the fact of God’s grace and forgiveness.

Douglas Moo: James, we have seen again and again, has a very practical theology. His eschatology is no exception. To be sure, James does not say much about ‘the last things’, although he says enough for us to place him securely within the typical New Testament ‘already/not yet’ perspective. In this passage, James urges us to think about life in light of the ‘end’ of things. God has established a day when he will culminate his programme of redemption and judge all human beings. We are to live each day in the light of that ‘end’ God has appointed: an end whose timing we cannot predict but whose coming is absolutely certain and ultimately significant. Too often, believers fall into the trap of thinking, like the ‘scoffers’ of 2 Peter 3, that Christ’s coming has been pushed so far into the uncertain future as to have no significance for the present. Quite the contrary, teaches James: Christ, the judge of all, including Christians, ‘stands at the door’.

Ralph Martin: How is the Lord compassionate and merciful if his children continue to suffer? He is loving and gracious in that he provides the strength to endure to the end, which is a denouement that consummates in glory and vindication for the faithful. That is a purpose of the Lord: to create his people as mature and complete persons of God and to uphold them so that in the teeth of persecution (1:1–4) they may enjoy the blessedness of the new world (4 Macc 17:17–18). Thus James closes his exhortation to patience (5:7) with a theodicy that rests on the assurance of the Lord’s goodness (5:11).

Daniel Doriani: This passage offers us many reasons to persevere in the faith. It comforts us in several ways. First, it shows us the Lord. He is near. He is the Judge and comes to set all things right. Second, it reminds us of Job and the prophets, who persevered to the end in great adversity. Yet above all, James takes us to the fatherly heart of God. He abounds in love and he is sovereign still. Knowing this, whatever our troubles, we can endure. We can persevere to the end and know the full blessing of God.

III. (:12) THE DANGER OF SWEARING AN OATH

A. Summary: No Need to Swear an Oath

“But above all, my brethren, do not swear,

either by heaven or by earth or with any other oath“

cf. “Cross my heart and hope to die” mentality of children swearing that something is true

Daniel Doriani: Students of James puzzle over the place of this verse in the structure of the epistle. Its connection to the rest of chapter 5 is a challenge. From Martin Luther to Martin Dibelius and beyond, theologians who question the structural cohesiveness of James cite 5:12 as a prime example of its tendency to drop disjointed aphorisms into the text. . .

Even if the meaning is clear, the exegetical and theological question remains: Why this teaching here? If James is a disorderly book, flitting from one topic to the next, 5:12 seems like prime evidence of the charge. Specifically, James 5:1–6 declares woe upon rich oppressors. Then 5:7–11 calls God’s people to patient endurance as they trust God to vindicate them. The book closes with a call to pray in all the circumstances of life (5:13–18) and a call to stand together in the faith (5:19–20). We wonder, then, what the prohibition of oaths has to do with either the theme of endurance in the face of oppression or the theme of praying and standing together in the faith.

Some say it is simply another sign of James’s concern about the proper use of the tongue, with no closer connection to the rest of the epistle.

Others see 5:12 as a final word on the proper response to trials. It retains the section’s interest in being prepared for judgment (5:9, 12). Further, it warns against a foolish response to the oppression described in 5:1–6, for people commonly respond to trouble and distress with unrealistic pledges to God. But it is better to be genuine than dramatic, better to mean what we say than to have unfulfilled, unrealistic vows hanging over us (cf. Eccl. 5:4). The warning against vows is, therefore, part of James’s call to patience and restraint in speech as in other daily behavior.

Still others see it as a genuine transition to James’s final section. The phrase, “above all” in James 5:12 is a literary convention meant to introduce final remarks. The topic, once again, is speech and the need to use the tongue to build community solidarity. Plain honesty is the first necessity (5:12), followed by prayer, confession of sin, and efforts to win straying brothers (5:13–20).

David Nystrom: “above all” (pro panton) means “most importantly” or “but especially.” However, given the care with which James has developed other themes—for example, the great stress he has placed on patience—it would be odd indeed if James were saying that his message concerning oaths he regards as the single most important in the entire letter. Rather, the term ought to be understood as “finally” or “to sum up”; that is, James is alerting his readers that the letter is about to conclude.

Any attempt to defend the present placement of this saying must show how it connects either with what has gone before or with what comes after. As many have noted, this logion appears out of place. However, when seen as an inappropriate use of the tongue in contradistinction to the proper uses pointed out in 5:13–18, it is clear that this verse has a rightful place here. This, of course, connects the verse with what comes after. But what about the preceding section? Martin believes that Reicke is correct when he argues that the swearing of oaths is a sign of the impatience displayed by the poor who live under the cavalier and unchristian treatment of the wealthy in their community. Since James has counseled these poor to be patient and to wait for the deliverance of God, Reicke’s insight may well be accurate.

Thomas Lea: [These words] warn against the use of a hasty, irreverent oath involving God’s name during a time of suffering or hardship. This logically follows the discussion of suffering in verses 10–11. Above all during our stress we should not resort to flippant oaths that communicate something about God to the world that we do not intend.

This prohibition bans the careless use of God’s name to guarantee the truthfulness of a statement. Christians who face suffering can be easily tempted to make a frivolous appeal to God’s name to bargain their way out of trouble or difficulty.

John MacArthur: The custom of swearing oaths was a major part of life in biblical times. It had become an issue in the church, particularly the predominantly Jewish congregations to which James wrote. Since swearing oaths was an integral part of Jewish culture, Jewish believers brought that practice into the church. But such oath taking is unnecessary among Christians, whose speech is to be honest (Eph. 4:25; Col. 3:9), and whose lives are to demonstrate integrity and credibility. For believers, a simple yes or no should suffice because they are faithful to keep their word.

To encourage believers to be distinctive in the matter of speaking the truth, James issues a command to stop swearing. There are four features of his command that need to be considered: the distinction, the restriction, the instruction, and the motivation.

Douglas Moo: The swearing that James here prohibits is not ‘dirty’ language as such, but the invoking of God’s name, or substitutes for it, to guarantee the truth of what we say. In the Old Testament, God is frequently presented as guaranteeing the fulfilment of his promises with an oath. The law does not prohibit oaths, but demands that a person be true to any oath he or she has sworn (cf. Lev. 19:12 – yet another instance in which James includes a topic mentioned in that chapter). Concern about the devaluation of oaths because of their indiscriminate use and the tendency to try to avoid fulfilling them by swearing by ‘less sacred’ things (cf. Matt. 23:16–22) led to warnings against using them too often (cf. Sirach 23:9, 11; Philo, On the Decalogue, 84–95). Jesus, it appears, went even further than this when he commanded his disciples not to swear ‘at all’ (Matt. 5:34). Jesus’ teaching in Matthew 5:34–37 is particularly important in understanding James’ teaching, because it looks as if James is consciously reproducing that tradition. . .

It is questionable whether either Jesus or James intended to address the issue of official oaths, oaths that responsible authorities ask us to take. What both have in mind seem to be voluntary oaths. Even with these, it is argued, the intention is not to forbid any oath, but only oaths that would have the intention of avoiding absolute truthfulness. This would seem to be the problem that Jesus addressed (cf. Matt. 23:16–22), and the evidence from Paul’s epistles show that he, for one, continued to use oaths (Rom. 1:9; 2 Cor. 1:23; 11:11; Gal. 1:20; Phil. 1:8; 1 Thess. 2:5, 10). Nevertheless, caution is required.

B. Stick to Your Simple Word

“but let your yes be yes, and your no, no;

so that you may not fall under judgment“

David Platt: In verse 12 James takes what seems like a hard left and starts talking about oaths. He says, “Your ‘yes’ must be ‘yes,’ and your ‘no’ must be ‘no,’ so that you won’t fall under judgment.” This is important, particularly in light of all that we have seen about our tongues in James. He is saying faith that perseveres is trustworthy in speech. The words from our mouths should be so consistent and dependable that they guarantee reliability.

R. Kent Hughes: Jesus and James are telling us we must never use “big guns” like “on my mother’s grave” or “as God is my witness.” Everyday speech and pulpit speech and courtroom speech are all to be the same—radically true!

Ralph Martin: Rather, what appears to be the case is the “voluntary” (Moo, 174) oath Christians feel must be given in order to ensure the integrity of their speech. The idea of condemnation (κρίσις) comes into operation when oaths are offered as a means of signaling the truthfulness of human intention. To conclude one’s remarks with an oath—which usually involved invoking God’s name—placed the speaker under even greater obligation to fulfill declared promises, and this in turn placed the oath-taker in greater danger of condemnation by God, since such speech was “more honest than other speech” (Davids, 190). For James (as for Jesus), believers should deal with one another in truth and honesty.